Eleven reasons why I don’t like ultraprocessed food (UPF)

Or: I wonder how many people I’m going to annoy today?

I feel like I’m courting controversy. What I’m about to write is probably going to annoy people. I’m writing this because I’m annoyed, and it would be reasonable to assume that this explanation of why I disagree with a certain parenting segment of social media may raise the hackles of the people with whom I am arguing against. But it seemed like not a bad idea to write down why I’m annoyed, if only to clarify for myself why I feel irritated whenever I see these comments. Because these comments I’m getting annoyed at? They actually sound pretty reasonable.

There seems to be a movement in parenting to promote healthy relationships between kids, food, and eating. These parents don’t label foods as ‘good’ or ‘bad’, they don’t stigmatise food, they don’t restrict food, and they believe in everything in moderation. They don’t want their children to grow up with disordered eating habits, or body image and self esteem problems, or be unduly and negatively affected by diet culture.

On the surface, none of these things are bad, or are thoughts that I disagree with. My contention comes from the broader context of these statements. I’ve typically seen these kinds of comments in discussions about what’s commonly considered junk food — biscuits (cookies), cakes, lollies, chocolates. According to this school of thought, these foods aren’t bad, and they are fine in a balanced diet, and you shouldn’t restrict them or talk about the calorie content or nutritional makeup of the foods because that is the way to disordered eating and food issues. And again, I don’t disagree that biscuits and cake and chocolate can have a place in a balanced diet.

My problem with these statements isn’t that I hate biscuits or chocolate or cake, or think that they should be banished from kitchens and lunchboxes*. My problem with these statements is that usually they are about ultraprocessed food, or UPF. And the thing that I really hate is the mentality that they are inevitable, that they are healthy (because look at the claims on the packaging! So healthy!), and that they are food. These are the things that run through my head as I read or hear people defending UPF:

Studies have shown that your brain can be altered by UPF, and some UPF activate the reward pathways in your brain the way alcohol and nicotine do. Without the flavourings and sweeteners and colourings, the industrial components of UPF wouldn’t even be recognised as food by your tongue and brain. What’s even more concerning is that for children who eat a lot of UPF, their physical check-ups and blood tests might show everything to be normal and the negative impacts of UPF may not be seen until they’re well into adulthood (Sources: Building an Ultraprocessed Mind episode of A Thorough Examination, and chapter ten of Ultra-Processed People by Chris van Tulleken).

Studies have also shown that UPF interferes with your hormones. A diet high in UPF lowers the amount of leptin in your body (the hormone telling you that you’re full), and raises the amount of ghrelin (the hormone telling you that you’re hungry). Your satiety signals are changed by UPF (Sources: Building an Ultraprocessed Body episode of A Thorough Examination).

The famous experiment** by Kevin Hall a researcher at the National Institutes of Health, where twenty people were taken into a clinical setting for four weeks and fed two different diets. For two weeks they ate a diet of whole foods, and for another two weeks they ate a diet of UPF that was matched for nutrients. They were allowed to eat however much they wanted, they were blinded to their weight, and wore loose fitting clothes so they couldn’t tell how their bodies changed. Kevin Hall was sceptical that UPF caused weight gain and designed the experiment to prove himself wrong. He expected no difference to the diets because the nutrients were the same. But then he found that on the UPF diet, people ate 500 calories more per day, and they gained both weight and fat (Sources: Building an Ultraprocessed Body episode of A Thorough Examination; What we know about the health risks of ultra-processed foods on NPR).

The importance of your gut microbiome for health and longevity, and the best way to feed your gut well is to reduce/eliminate UPF, as well as eat a wide variety of plant foods (Sources: Metabolical by Robert Lustig, Food Special with Tim Spector episode of the Just One Thing podcast).

There is also research that shows detrimental effects on our bodies when what we taste does not match the substances we are consuming; we are being tricked by artificial flavours, colours, textures, and even vitamins (Source: The End of Craving by Mark Schatzker; see also The Dorito Effect by Mark Schatzker and Hooked by Michael Moss).

The food scientists and engineers who design these food-like substances don’t eat the products they create — ‘Like other former food company executives I met, he [Robert Lin, once the chief scientist for Frito Lay] also overhauled his own diet to avoid the very foods he once worked so hard to perfect. There were few, if any, processed foods in the cupboards he opened for me.’ That quote is from Salt Sugar Fat by Michael Moss (page 314 of the 2013 hardcover edition, if you’re playing along at home), and it is a line that has stuck with me years after reading it. If the people who know what is really in these foods choose to stay away from them, should we be okay eating them and feeding them to our kids? What do they know about these products that their bosses at the large food corporations don’t want us to know?

Research that shows UPF is fine in a balanced diet could be (probably is) funded by large food companies — like the Global Energy Balance Network, a not-for-profit organisation that supposedly researched the causes of obesity and found that lack of exercise was the problem. Arguably the bigger problem is that this organisation was funded by Coca Cola. This is a blatant example of the food industry getting its hands dirty, but more subtle ways of the food industry influencing science abound (Sources: Unsavory Truth by Marion Nestle, Appetite for Profit by Michele Simon, and Metabolical).

The marketing of UPF to convince parents that it’s healthy and you can feed it to your kids guilt-free, but ALSO the food industry’s power in making sure there are loopholes in legislation so they can still advertise to children (Source: Kid Food by Bettina Elias Siegel)

Large food corporations selling to school cafeterias (and getting their branding in schools), the problems with school lunch programs (not enough time for kids to eat, no real kitchens for food prep, not enough funding, the food industry’s influence on the nutrition standards that school meals have to follow (Source: Kid Food).

The leaders of the largest food companies know, and have known for years the problems with their foods, and the problems with UPF/obesity are not unlike the problems with tobacco a few decades earlier. It’s the same playbook, and even the same companies — Philip Morris, the tobacco company, acquired the two largest food manufacturers, General Foods and Kraft, in the 1980s (Source: Salt Sugar Fat; also see point 6).

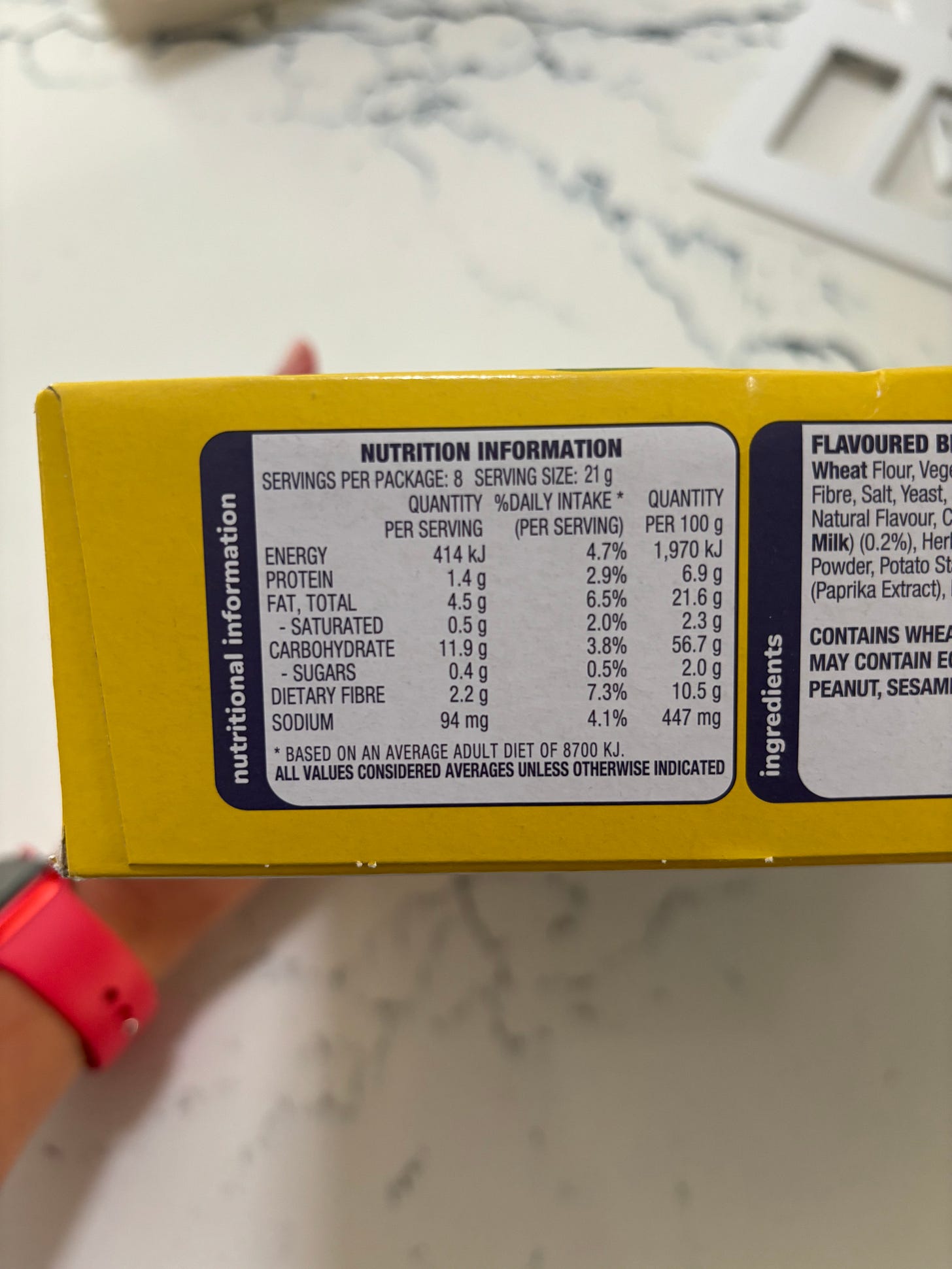

The large food companies and interest groups have such power in the creation of legislation, nutritional standards, and safety standards; it’s almost obscene. (Source: Food Politics by Marion Nestle, Soda Politics by Marion Nestle, Safe Food by Marion Nestle). They heavily influence the direction of the conversation about food and nutrition, and as one tiny example, I’m pretty sure that the reason nutritional labels in America are worse than the ones in Australia is because Big Food is all over it. They don’t tell you nutrients per 100g, just per serve, which wildly differs by product so it’s hard to do easy comparisons of different products — that’s by design. Big Food didn’t even want nutritional labels at all.

(Pictured above is the nutritional information panel on Bluey cheese flavoured crackers from Australia. Yep, it’s a UPF and no, I have not managed to entirely eliminate UPF from our diets. But look at the column on the far right! Quantity per 100g! Isn’t that such a wonderful and useful column?)

Knowing all of this, and then seeing comments that there is no such thing as bad food, or that we shouldn’t stigmatise certain foods, irritates me no end. Sure, there is no such thing as bad food — as long as what you’re talking about is actually food. But often this is said in relation to UPF, an engineered food-like substance. And why shouldn’t there be a stigma around UPF? I don’t think anyone would say that we should destigmatise cigarettes, but for some reason UPF gets a free pass even though it’s the same companies, with the same tactics, convincing people to consume something the companies know are bad for them.

There is a clear rebuttal here to what I’m saying. What about people who are time poor, or financially not well off, and they can’t afford fresh fruits and vegetables or to be cooking from scratch every night? What about just wanting a bit of comfort because everything else in your life is hard? What if you can’t afford to waste food and you aren’t sure if your kids will try the new thing but you know they will eat the boxed mac’n’cheese? (See: How the Other Half Eats by Priya Fielding-Singh, Nickel and Dimed by Barbara Ehrenreich, and Down and Out in Paris and London by George Orwell).

These are legitimate concerns, and I think it also speaks to how food is such a broad topic that discussions about it is not always just about what we put in our mouths. I emailed Priya Fielding-Singh after I read How the Other Half Eats and told her that I thought her book wasn’t really about food, but it was about poverty and inequality in America told through the lens of food. There are other problems with American society that are unrelated to my dislike of UPF, like the lack of annual leave, sick leave, paid parental leave. The lack of lunch breaks. The insufficient funding of public education and lack of public health. The lack of subsidised childcare. The lack of security and freedom (yes, I said it — the lack of freedom. In America). This is a great country to be in if you’re rich, but a terrible one to be in if you’re poor.

This makes it really hard for everyone to be able to eat a diet of mostly whole foods, and feed families with meals cooked from scratch most nights of the week. I’m mad about this too! To be able to say that you can cook from scratch for most meals and feed your kids a lot of fruits and veg takes time, money, and planning. There is no shame in not being able to do this.

But none of that changes the eleven points I made earlier about UPF about how, generally speaking, it is not doing your body any favours and there can be long-term health consequences of consuming a diet high in UPF that we are only just starting to understand. The aggressive marketing of these foods, the underhanded tactics of the companies selling these foods, and the power they have in affecting legislation and policy are problems that should make us all mad, and saying we should stop labelling food as ‘bad’ or we should destigmatise food is missing the point about the harmful behaviour of the food industry. It feels like body acceptance has gone too far in defending and accepting UPF and that’s what I’m annoyed about.

*I really genuinely don’t hate biscuits, chocolate, and cake. I love excellent versions of these foods, made with good ingredients and skill. What I dislike is most of the cookies and chocolate you find in a typical American supermarket. But I’m not one of those people who don’t like dessert or don’t like chocolate, not that there’s anything wrong with that either.

**I’m not sure when something counts as ‘famous’. Would anyone who hasn’t spent the past couple of years reading about the food industry and UPF know about Kevin Hall and this experiment? All I know is that his name and this study has been mentioned in pretty much every book, article or podcast about UPF I’ve read or listened to. It seems pretty famous. But he might not be asked for his autograph when he’s just walking down the street.

I definitely agree with this sentiment! But I must say the Cheez-Itz in my closet are very appealing lol.